It’s been a little over two weeks since I was briefly encouraged, then relentlessly pummeled on Twitter for posting pictures of two boxes of Lord of the Flies next to the garbage. I playfully posted that I was doing a Marie Kondo-like cleanse by decolonizing the book shelves of my school. The reactions were swift, visceral, and pointed. I’ve had some time to reflect, time to write privately, and time to formulate a more reasoned response than one I might have given in the moment.

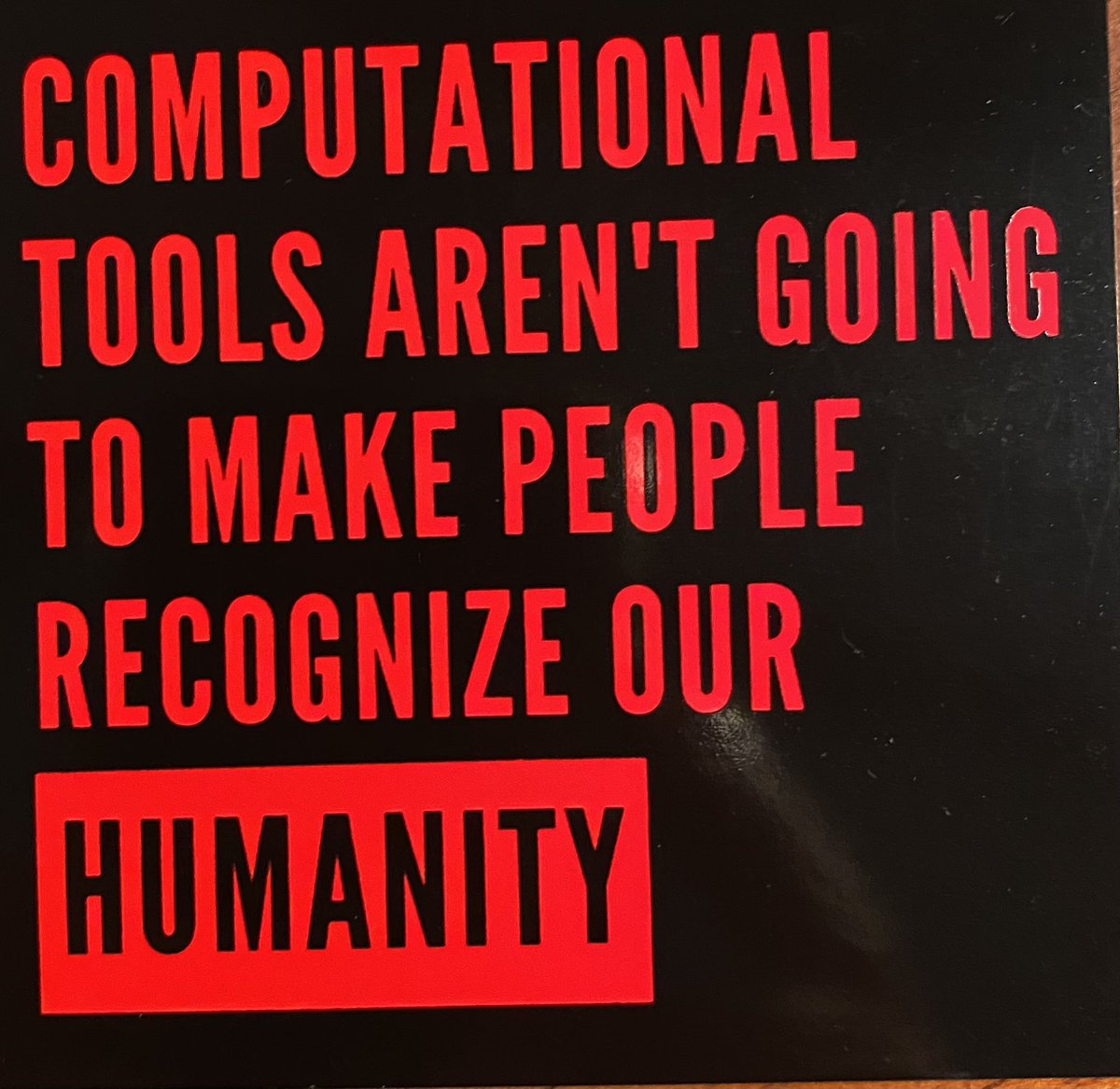

Yet, I worry that my delay is also part of the problem with moving to a more equitable list of books. I wonder that in my taking time to respond, I have granted de facto power to those who rail against the disruption of the “literary canon”, resistors who uphold the status quo. We know that change in education is slow and I’ve observed that some fear it more than others. This systemic resistance to change sometimes requires what appear to be radical acts of disruption.

I’ll admit that I made an impulsive decision to post this box of books to Twitter, but the decision to discard them was at least two years in the making. It started in 2019 when I spent a summer learning about First Nations, Metis, and Inuit ways of knowing, reading Indigenous authors, and following Indigenous thought leaders on Twitter like Jody Kohoko and Josh. I joined #4BigQuestions and #AntiracistReads listening to Pamala Agawa and Colinda Clyne. With the colonial lens of my upbringing now in full view, the need to shift the content and approach to instruction came into focus as part of Truth and Reconciliation, the educator’s call to action, and so I made an emotional commitment to change.

But there was more to this story of discarding books which came through listening to students in our Diverse Student Union, Black students who recalled being the only student of colour in a class where white students read the “n-word out loud”. Reading Lord of the Flies had seared a traumatic memory in their minds. Grade 10, grade 11, and grade 12 students referred to specific moments in class citing this text as a source of pain.

Feeling the need for action, I rushed to post to Twitter in a week where I feared my own foot-dragging and invisibility which made me safe and comfortable while our Director, Camille Williams-Taylor, made bold, informed, and necessary moves to curb the trauma experienced by racialized students in the classroom. The ban on racial slurs and epithets was passed and this gave me the impetus to discard the one text that so many students over the years had named as the source of their classroom trauma. I had the support of my principal so what I was doing felt right.

What I was not prepared for was the response.

That impulsive decision had me experiencing an onslaught of attacks against me which ranged from gender to race, to my role as an educator; I was accused of “virtue signalling”, succumbing to the dangers of “woke culture” and being a “white saviour”. An educator in the US warned me that I had been posted on the Twitter feed of a radical conservative with thousands of followers, James Lindsay, and she suggested that I delete the post and lock my account for my own safety. The Twitter response seemed out of proportion to the action. Why would so many people so far away from my geographical location decide to vilify me and attempt a public takedown on Twitter?

I did not understand anything other than my need to sort through the voices to listen, reconsider, and resist the attack. I locked my account, my blog, and stayed off Twitter for a week. I then wrote myself a pep talk:

I understand that you’re afraid. That’s human and those attacking you are fearful too. So tell your truth, honestly and clearly. Say what happened, where it took you, what you’ve learned, and where you stand. Because if you can’t stand up against a status quo that so clearly causes trauma for students, if you can’t absorb the invisible anger thrust against you, then you aren’t ready for this fight. You have doubters and critics and maybe even enemies, but your decisions are not for you. Resist the urge to cave in when the anger appears. Resist the pull to comfort. Resist the lull of the status quo.

Although I might regret some part of my impulsive post, it taught me that a genuine commitment to student well being requires active listening to the marginalized, active changes in the status quo, persistence in the face of personal attacks. Reflection, in this case, brought me closer to my own understanding of resistance.